Activity: Illustrated reading

Host: Moray House Trust

Date: Tuesday 31st January 2023

Time: 11.00 AM Guyana/ 3.00 PM UK

YouTube: https://youtu.be/QuZjDDGRv1U

Over the years, Moray House Trust has worked to add to the stock of knowledge in the public domain about Guyanese artists. So, for example, we have hosted events or prepared short films about the work of Philip Moore, Bernadette Persaud and Ron Savory. On Tuesday 31st January 2023, we hosted a Zoom screening of this short film about Aubrey Williams with several members of Aubrey’s family in the audience.

INTRODUCTION

Aubrey Williams was one of several Guyanese writers and artists of the mid C20 whose thinking was profoundly shaped by the time they spent in the hinterland, among our Indigenous peoples. Wilson Harris was another, as was Ivan Forrester, also known as Faro. They were all, of course, coastlanders. There have been many distinguished artists and thinkers among our Indigenous peoples: Stephanie Correia, George Simon and Ossie Hussein to name but a few.

Aubrey Williams was born in Georgetown in 1926 and departed its shores at the age of 26. Much of this reading is about the time he spent in Hosororo as an agricultural engineer. Hosororo, as Aubrey tells us, means ‘noise of water’ or ‘noisy water’. Ironically, as Williams discovered on his return visit in 1986, the waterfall at Hosororo, the source of its name, had all but disappeared courtesy of a since-abandoned attempt to set up a hydro-power project.

Williams returned to Guyana periodically, for example, in 1970 to paint the Timehri series of murals. When he returned in 1986 to restore the murals, a film crew accompanied him to make a documentary. This documentary is called Mark of the Hand, Aubrey Williams. It is available online (for a small fee) and incorporates a great deal of his artwork.

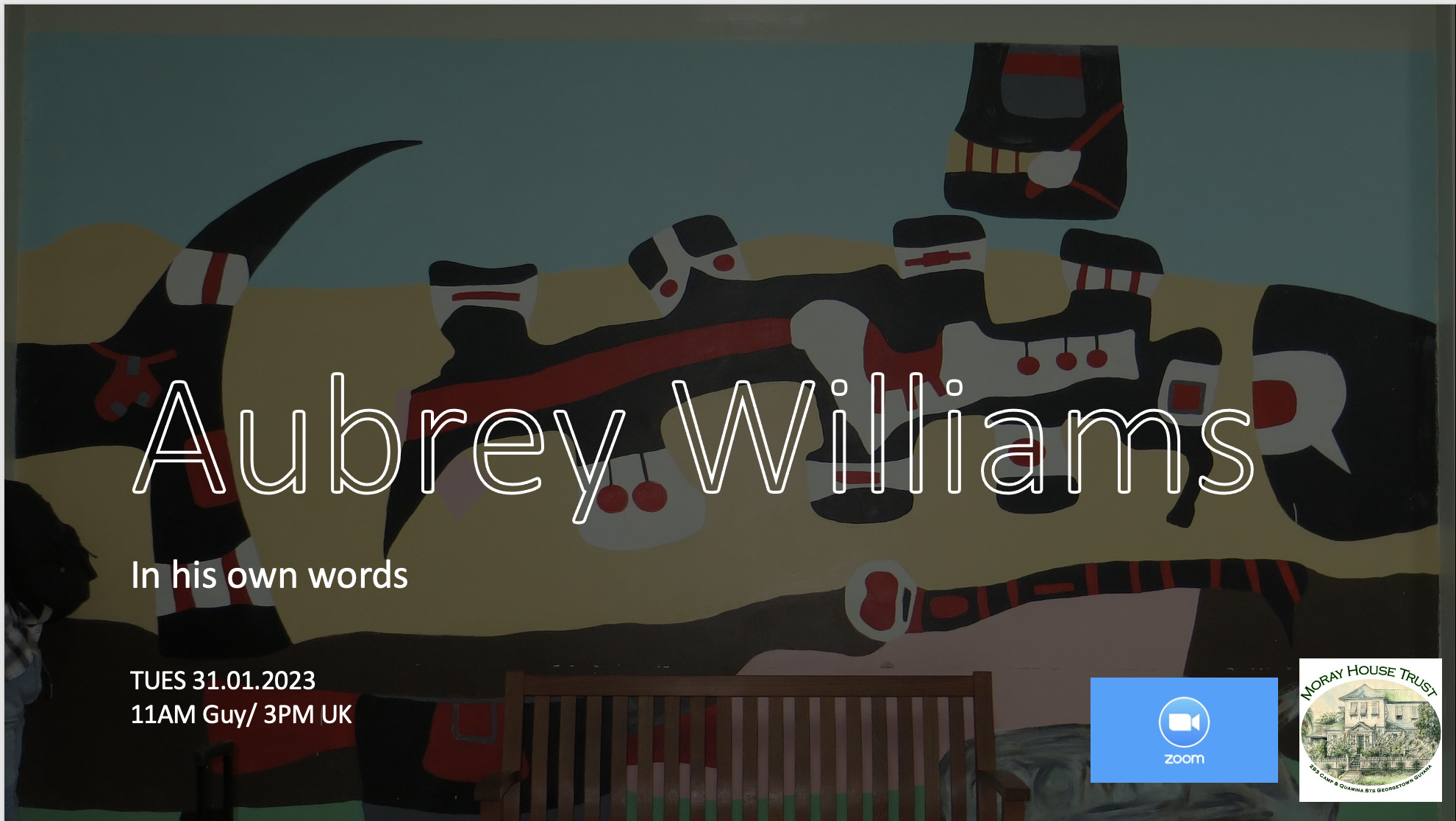

At least one of Aubrey’s Timehri murals will have been seen by every Guyanese who travelled through Timehri Airport in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. Two of his murals, Kamarau and Kaituma, adorned the upper exterior walls of the airport building and were visible to passengers as they approached the terminal building. Another, Tumatumari (pictured in the flyer), was on the ground floor, in the waiting room for arrivals. It is now in the passport area for departures. Whether these works of art registered in any meaningful way is another matter. There was, and still is, absolutely no signage, to indicate anything about the artist or the subject matter of the murals. This is a regrettable omission. All of the artwork at the airport should be clearly labelled and contextualised.

Aubrey had a clear idea of the source of inspiration for his art and was perfectly capable of articulating it. Whether he was able to find a receptive audience for his thinking was another matter. Thirty plus years after his death, his work is back in vogue in the metropolis. But there has still been little attempt to investigate links between his early work and the symbols and beliefs of our indigenous peoples in Guyana. This is another omission.

We owe, therefore, a profound debt to Anne Walmsley, a British art critic and scholar, specialising in Caribbean art and literature. It is her transcription that forms the basis for this reading. Her compilation of interviews with and essays by and about Aubrey Williams, called Guyana Dreaming, the Art of Aubrey Williams, appeared shortly after Aubrey’s death in 1990 and went some way towards redressing these gaps and silences.

Finally, a word of thanks to Stanley Greaves, for lending his voice and guitar playing to this attempt to piece together a few more fragments of our cultural heritage. Thanks also to Maridowa, Aubrey’s daughter, for sharing images of the family.

RECORDING: https://youtu.be/QuZjDDGRv1U

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES:

Documentary: Mark of the Hand: Aubrey Williams, British Film Institute