Activity: Lecture

Co-ordinator: University of Guyana, Moray House Trust

Date: 7th May 2012 Continue reading “Floods of Fire”

A Colloquium on Copyright

Activity: Lecture

Co-ordinator: Petamber Persaud

Date: 24th April 2012 Continue reading “A Colloquium on Copyright”

Eight Short Films

Activity: Film screening

Co-ordinators: Cine Guyana, Moray House Trust and University of Guyana

Date: 20th April 2012 Continue reading “Eight Short Films”

Citizens’ Charters, Good Governance and Good Business

Activity: Workshop

Co-ordinator: Transparency Institute Guyana Inc (Nadia Sagar)

Date: 20th April 2012 Continue reading “Citizens’ Charters, Good Governance and Good Business”

Virtual Politics: The Internet and Guyana’s 2011 Elections

Activity: Book launch

Co-ordinator: UG Communications Centre, Moray House Trust

Date: 12th April 2012 Continue reading “Virtual Politics: The Internet and Guyana’s 2011 Elections”

Young Writers’ Workshop Part One

Activity: Workshop

Co-ordinators: Moray House Trust (Paloma Mohamed, Vanda Radzik) with the kind assistance of Ian McDonald, Joyce Jonas,

Sponsor: ScotiaBank.

Date: 12th April 2012 Continue reading “Young Writers’ Workshop Part One”

An Introduction by David Dabydeen to his two new books

Activity: Book reading

Co-ordinator: Moray House Trust

Date: 2nd April 2012 Continue reading “An Introduction by David Dabydeen to his two new books”

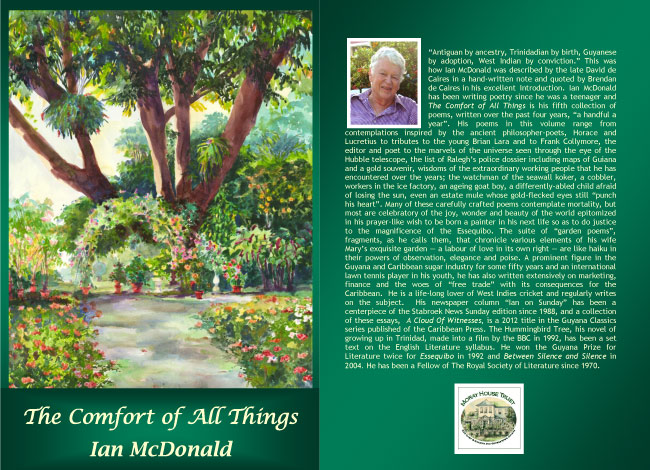

An Evening with Ian Mc Donald & Young Readers

Activity: Poetry readings, book launch

Co-ordinator: Moray House Trust

Date: 30th March 2012 Continue reading “An Evening with Ian Mc Donald & Young Readers”

A Look at David Dabydeen’s Literature by Al Creighton

Source: Sunday Stabroek

Date: Sunday, 25th March 2012

Some years ago, David Dabydeen did a presentation on the close historical relationship between British art and sugar, articulating the association of art with the financial gains of African slavery in the West Indies. He spoke specifically to the history of Booker Tate in British Guiana, and ironically titled the presentation ‘Art of Darkness’.

Of equal significance are Dabydeen’s close studies of British art, the history of blacks in Britain in the eighteenth century, abolition and African slavery in the Caribbean. The work of English eighteenth century artist William Hogarth provided the source of his interest in blacks in British eighteenth century art and of at least two of his major works Hogarth’s Blacks (non-fiction) and A Harlot’s Progress (fiction). The great English landscape (and seascape) painter JMW Turner, and in particular the famous Turner painting Slave Ship (1840) inspired Dabydeen’s best poetic work so far – a long poem called Turner (1994).

‘Art of Darkness’ is a pun on Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness which has served Dabydeen very well as source of inspiration and intertextual engagement, a literary strategy that has been a major part of his work and artistic interest.

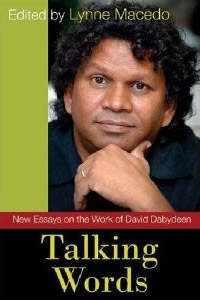

As a matter of fact, intertextuality is one of the main themes in Talking Words (University of the West Indies Press, 2011) edited by Lynne Macedo, “New Essays on the Work of David Dabydeen” with ten chapters by different critics. Even the title—Talking Words—seems to go into double entendre. It is most likely taken from “Ma Talking Words”, a poem in Dabydeen’s Coolie Odyssey. But it also suggests a play on words with reference to Dabydeen’s own use of language. The book could be various critics talking about words, the major tool of Dabydeen’s trade, and the words he has produced. But it could also be about talking words, meaning words that talk, and a reference to Dabydeen’s use of standard language and non-standard Creole, and what he can dramatically do with words. It might also be a reference to this artist’s latest novel Molly and the Muslim Stick (2008) in which a talking walking stick becomes a major ‘character’.

Lynne Macedo explains that the volume “contains the most recent collection of critical writing that is focused exclusively on the fictional output of this acclaimed poet and novelist. Its publication has been designed to coincide with that of Pak’s Britannica: Interviews and articles by David Dabydeen, and to offer a fresh but complementary look at all of Dabydeen’s major works by Caribbean scholars from across the world. […] The range, scope and originality of these chapters clearly demonstrate the continuing interest in critical appraisal of all of Dabydeen’s writing.” Pak’s Britannica (UWI Press, 2011) is a companion volume to one also edited by Macedo, an Associate Fellow of the Centre for Caribbean Studies at the University of Warwick where Dabydeen is Professor of Literature. Macedo herself is a leading scholar of West Indian literature who in 2010 was one of the coordinators of a Warwick conference on – Art and the Environment held in Guyana. An earlier volume of critical papers appeared in The Art of David Dabydeen edited by Kevin Grant.

This collection of essays takes special interest in language and intertextuality. As Macedo points out in her discussion of the contribution of Jenny De Salvo, there is discussion of intertextuality although her “interest is … from a linguistic perspective”. She gives “a detailed exploration of ‘the variety of registers and languages’ that Dabydeen employs in The Intended” (his first novel, 1991), while, “by highlighting his numerous allusions to canonical works … she clearly demonstrates the subversive qualities of Dabydeen’s novel”. anguage and intertextual allusions are also leading subjects in the other chapters, which are grouped under Part 1: Poetic Reappraisals focusing Dabydeen’s poetry, and Part 2: (Re)Reading the Novels. In Part 1 Monica Manolachi discusses “Cultural Hybridity”, Anjali Nerlekar analyses what she calls Dabydeen’s “Poetry of Disappearance”, while Nicole Matos examines ‘Audience, Authenticity and the African Imaginary’ in both poetry and prose in her study of Turner and A Harlot’s Progress. In the other chapters devoted to prose, Russell West-Pavlov deepens the intertextual explorations of “Conradian Journeys” in a reading of Disappearance, while Abigail Ward’s interest is in “The Slave Narrative Genre”, which Dabydeen “Re-presents” in Harlot’s Progress. Like Matos, Erik Falk overviews the poetry in addition to the early novels and the latest, Molly and the Muslim Stick, in which he finds an “exoticist aesthetic”, while Jutta Schamp sees in that same fiction “Trauma, Literary Alchemy and Transfiguration”. A reading of the two later novels interest both Liliana Sikorska and Michael Mitchell, as Sikorska discusses “Re-scripting Genealogies in Our Lady of Demerara and Mitchell focuses “Magic and Realism in Dabydeen’s Recent Fiction”.

The book, as a whole, presents its readers with critical discourse of very high quality, with many incisive revelations about some of Dabydeen’s most interesting preoccupations, not only opening windows to new approaches to his work and devices, but heaping high praise upon them. Mitchell, for example, quotes Kevin Davey in suggesting that one should “turn to Dabydeen if you want to know where (Black writing in Britain) could and should be going”. That is indeed a compliment of the highest order, to which Mitchell adds his observation that in his recent fiction Dabydeen moves away from straight realistic fiction into absurdism and magical realism, preoccupations that disappoint those critics who were looking for normal English fiction in Our Lady of Demerara and a child abuse case study in Molly. They both, however, operate “outside of the logic of realism”.

Like West-Pavlov, Manolachi, Macedo, Nerlekar and other contributors, Mitchell highlights the allusions and stylistic delving into other texts in which Dabydeen takes an often serious but sometimes mischievous delight.

There are numerous citations as he carries on an infinitely intriguing discourse with not only the painters Turner and Hogarth, and the novelist Conrad, but with Shakespeare, especially The Tempest, in a manner that renders his work that much more profound. In some cases he wishes to pay homage to great West Indians Wilson Harris and VS Naipaul. While he treats them with reverence in Disappearance and Our Lady, it is hardly the same in his presentation of the character Vidia in The Counting House, a novel that does not get very much attention in Talking Words. But several other works to which Dabydeen alludes are cited: Naipaul’s The Enigma of Arrival, Harris’ The Secret Ladder, Lamming’s Water With Berries, a parody of TS Eliot’s Wasteland, Dante, Wordsworth, Blake, inter alia.

Dabydeen’s language is another area of major interest in Talking Words. There is his versatile use of Standard English in his appropriate stylistic variations, in addition to his very keen ear for Guyanese Creole. The contributing critics give very good account of the linguistic preoccupations in their close studies of the poetry in particular. That is why the errors in the collection are surprising. They contend that while Slave Song is mostly written in Guyanese Creole, “by contrast” the use of Creole in Coolie Oddysey is “moderate”. This is not the case. It is true that Slave Song achieves a certain fierceness and violence in the brutality of its language, complete with sexual explicitness. But the language in Coolie Odyssey is hardly more reticent. What happens is that much of the crudity in the earlier volume comes from the fact that the Creole is a non-standardised language that can pose challenges when rendered in writing. Despite Dabydeen’s keen ear he sometimes struggles with this task in Slave Song. In his second collection, however, his writing of the language is more efficient and is set down with greater fluency. But it is the language that Dabydeen would have heard in Canje in Guyana’s County of Berbice, hardly outdone by the sexual references in Slave Song. Secondly, there seems to be some amount of confusion among the critics about the identity of the personae in Slave Song, which is basically about African slaves. Quite often in Talking Words there is reference to the Indo-Guyanese or the Indentured Indians when it should be about the black enslaved.

There is little doubt about that because Dabydeen has related in interviews that his interest was in the blacks both in his research and in that first volume. He related how he was confronted after a public reading from the book by a hostile member of the audience who in accusatory tones suggested that he should stick to writing about his own people.

He felt affronted and sufficiently angered to think about writing Coolie Odyssey. It is true, however, that Dabydeen’s major concern was the plantation, which was the hostile habitat of both race groups, so the experience that he writes about in Slave Song could well refer to both Africans and Indians.

To date Dabydeen has published three books of poetry and six novels. He already had two collections of poems before his first novel in 1991, but since Turner in 1994 all his work has been fiction.

Manolachi comments in Talking Words about his emphasis on hybridity in Turner, and the way he turns a painting about a slave being thrown overboard from a ship in the ocean to a poem that encompasses the whole trans-Atlantic experience for Africans, Indians and Europeans alike. It is a poem enriched by the subject of slavery, mythology, Hinduism and other cultures, and is Dabydeen’s best work of poetry to date, despite the two prizes won by Slave Song.

Dabydeen steadily progressed into the circle of leading Caribbean and post-colonial authors, and is among the foremost celebrated writers of whatever background in Britain. The appearance of yet another volume of essays on his work indicates the rise in critical attention that plays its part in establishing him as a major writer.