Title: Martin’s Mantras: Martin’s thoughts on writing poetry

Item: Commentary

Speaker: Dr Ian Mc Donald at Young Writers Workshop

Date: April 2012

You Tube link: Martin’s Mantras

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U4OD8zrEHf8 Continue reading “Martin’s Mantras: Martin’s thoughts on writing poetry”

Hugh Cholmondeley was an exemplary citizen of Guyana and the world

Source: Stabroek News

Date: 19th August, 2012

Moray House Trust salutes the example of the late Hugh Cholmondeley as an exemplary citizen of Guyana and of the world. He was a man of integrity and humanity with a sharp intellect and was a master at incisive analysis. He was always interested in current events and volunteered his services to many civil society and rights-based institutions in Guyana.

Hugh was a great friend of the late David de Caires and he was a regular visitor and frequenter of Moray House (David’s family home, now established as a cultural trust) where he actively contributed to the conversations and debates on varied subjects that took place there in the company of Martin Carter, Miles Fitzpatrick, Lloyd Searwar, Ken King, Ian McDonald, Rupert Roopnaraine, Joe Singh, and David himself, amongst others.

Hugh Cholmondeley’s experience and skill as a communicator, mediator and negotiator was renowned and his style, good work and ready patriotism will be much missed. His legacy will forever stand in Guyana.

Our condolences go out to his wife Marianne and children Deborah and Adrian, his former wife, Elizabeth Wells and daughters, Tracey, Melina and Cathy, son-in-law Nigel Hughes and to his brothers, Keith and Colin and their respective families noting that Colin Cholmondeley is one of the Directors of the Moray House Trust.

May he rest in peace.

Yours faithfully,

Vanda Radzik

for Moray House Trust

“Not a book launch”

Source: letter in Stabroek News

Date: Friday September 2nd 2011

http://www.stabroeknews.com/2011/opinion/letters/09/02/not-a-book-launch/

Dear Editor,

Limited as my exposure has been to Clem Seecharan’s authorship, ie, to Sweetening Bitter Sugar, I have been an admirer of his scholarship. All the more reason that I was disappointed to learn from SN of August 21 of the launching of his latest publication: Mother India’s Shadow over El Dorado: Indo-Guyanese Politics and Identity: 1890-1930’s in the presence of what you describe as “a small gathering.”

It occurred to me that as an educationist and historian, Professor Seecharan should recognise that the history of a country’s people belongs to all of them; and that all without exception, should be ‘educated’ about their multicultural heritage – from which we cannot ever be insulated, even though at the same time the implication of ‘shadow’ is hardly a positive reflection.

However coincidental may have been the Professor’s involvement in this discussion, it may be useful to recall that he enjoys a position of leadership that should enable him to guide special interests towards the wider membership of the human village.

It is impossible, for example, to be both ‘Guyanese’ and ‘separate’ at the same time. It is the continual and sincere embrace of our respective identities which contributes to our being wholly Guyanese.

I much prefer therefore that I have misinterpreted the message emanating from SN’s recital. Irrelevantly perhaps, I recall not so long ago, bemoaning the celebration of Shivnarine Chanderpaul as an ‘Indian’ for feats he performed as a ‘West Indian’ batsman.

Yours faithfully,

E B John

Editor’s note

The occasion was not a “launch” of Prof Seecharan’s new book; it consisted of readings of excerpts and a discussion. The work is not available locally as yet, and it is always possible that when it is, there might be an official launch which would be open to the public at large. Moray House, the de Caires family home, accommodates only about 25 people, and the guest list consisted of persons suggested in the first instance by Prof Seecharan, and in the second, by the de Caires children. Prof Seecharan had a long association with the late David de Caires and that association continues with his family. Once it was learned that the Professor was in Guyana on a brief personal visit, the opportunity was taken to arrange an impromptu reading and discussion of Mother India’s Shadow…

Clem Seecharan discusses new book on Indian-Guyanese politics, identity

Source: Sunday Stabroek

Date: August 21st 2011

http://www.stabroeknews.com/2011/archives/08/21/clem-seecharan-discusses-new-book-on-indian-guyanese-politics-identity/

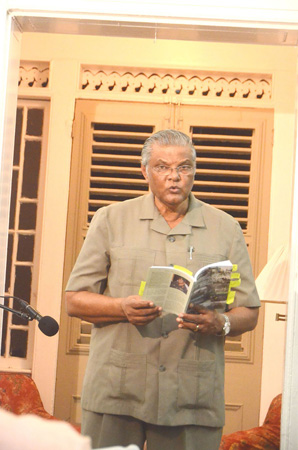

“For more than an hour last Wednesday, Professor Clem Seecharan discussed and read excerpts from his latest publication Mother India‘s Shadow over El Dorado: Indo Guyanese politics & Identity 1890s-1930s outlining to the small gathering at Moray House some significant changes that occurred in the East Indian community during this period.

Between the 1890s and 1930s, the East Indian community in British Guiana experienced major political and social changes which Seecharan asserted were significantly influenced by the rise of an Indian intellectual class and the presence of a liberal press.

Seecharan is a Professor of Caribbean History and has been the Head of Caribbean Studies at the London Metropolitan University since 1993. He has produced several books including Bechu: ‘Bound Coolie‘ Radical in British Guiana, 1894-1901 and Sweetening ‘Bitter Sugar’: Jock Campbell, the Booker Reformer in British Guiana, 1934-66.

Describing the work as one of his most challenging publications to date, the UK-based historian and writer said that he depended on writings which appeared in the Daily Chronicle, New Daily Chronicle and the Daily Argosy—three popular newspapers in British Guiana at the time. The newspapers, he pointed out, provided locals with the opportunity to express themselves via letters and in columns. “In the colonial period, when this democracy was severely circumscribed people had the opportunity in the press, in the liberal press to ventilate their opinions. And they would cuss the governor, and they would cuss the chief secretary and they could do all of these things,” he said. He noted that during this period several East Indians—such as Peter Ruhoman and Lala Lajpat, among others—had columns in the newspaper.

Seecharan noted that East Indians in British Guiana were significantly influenced by the Gandhian movement and the Indian nationalist struggle. A lot of what happened in India was reported in the local newspapers at that time Seecharan noted.

However, while there was greater exposure to a body of knowledge, there was very high illiteracy among Indian girls, due in part to legislative changes, particularly the introduction in 1902 of the Swettenham circular promulgated by Governor Alexander Swettenham.

This circular, which was implemented in collaboration with the planters in the country, did not make education compulsory in the rural areas if a child’s parents objected. Previously the compulsory Educational Ordinance of 1876, stipulated that in Georgetown and New Amsterdam children had to go to school up to the age of 14 but in rural areas they had to go to school up to the age of 12. However, the Swettenham circular made it clear that in rural areas if Indian parents objected to the children going to school, the compulsory education ordinance should be waived and the parents not be prosecuted.

J I Ramphal, was one of the persons who fought against this, challenging the planters, the Brahmin priests and the large number of persons who did not feel this circular should go. According to Seecharan, Ramphal’s fight was in part influenced by the nationalist movement in India. He would point to cases in India where women in India graduated from university with degrees and to their role in the Indian National Congress.

Seecharan noted though that during this period there was a call for the East Indian community to look to the motherland for inspiration and to reclaim something of themselves, just as the Africans were doing. “So when a man like Joseph Ruhoman in 1894 delivered the first lecture given by an Indian in the Caribbean, he was saying you must as Indians in British Guiana emulate what the African people are doing in this country,“ the professor said. Ruhoman, Seecharan continued, was talking about an educated lower-middle class which was redefining the parameters of these societies and laying groundwork for liberal democratic traditions.

According to Seecharan, Ruhoman was saying to the East Indian community that they needed “to go beyond the idea of the coolie.”

“You’ve got to begin see yourself as people who belong here and who have a contribution to make and to move beyond the idea of the coolie, you’ve got to give yourself the way African people and coloured or mixed race people and Portuguese people and so on were doing in this city,” the professor said.

Many people were creating a notion of homeland that was totally at variance to their situation at home because it was too painful to revisit. He made reference to the “cultivation of collective amnesia.” The professor noted that people in the sugarcane fields had a powerful concept of ancient history taken from great Hindu texts, especially the Ramayan.

In reality, the majority of East Indian immigrants who were in British Guiana at the time had escaped from parts of India where famine and plague were chronic. He pointed to the high percentage of child widows (12-13 year-old girls) who came to this region because they had nowhere to go when their husbands died in India. According to Seecharan, two-thirds of the women who came to British Guiana and to Trinidad as indentured immigrants came here unaccompanied.

Many of the East Indians who remained here, dreamt of a “golden age” which they would experience in British Guiana—a notion which was reinforced by the myth of Eldorado. This utopian vision of British Guiana, Seecharan noted, was key for survival here.

Seeharan said that the book is a body of knowledge that would hopefully move the people beyond the body of problems we have been dealing with for a long time. He noted that there were controversial issues addressed in the book which have implications for the racial division which exists today, mentioning that at one point some spoke about creating an Indian colony here within the British Guiana Indian Association.

Copies of the book are expected in the country shortly and will be available at the Austin’s Bookstore.”

Growing up in British Guiana 1945-1964

Title: ‘Growing up in British Guiana 1945-1964’

Reader: Dr Rupert Roopnarine introduces Joe Singh’s fifth book

Date: December 2011

You Tube link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JYqpF7wuuaA Continue reading “Growing up in British Guiana 1945-1964”

Growing up in British Guiana 1945-1964

Title: ‘Growing up in British Guiana 1945-1964’

Reader: Major General (rtd) Joe Singh

Date: December 2011

You Tube link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kVxhfKiptiI Continue reading “Growing up in British Guiana 1945-1964”

Growing up in British Guiana 1945-1964

Title: ‘Growing up in British Guiana 1945-1964’

Reader: David Dabydeen

Date: April 2012

You Tube link: David Dabydeen reads an extract from Joe Singh’s fifth book

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vvb14INelzo Continue reading “Growing up in British Guiana 1945-1964”

How I write poetry

Title: ‘How I write poetry’

Speaker: Ian Mc Donald at Young Writers Workshop

Date: April 2012

You Tube link: ‘How I write poetry’ by Ian Mc Donald

A Talk with Opinions

Activity: Lecture

Co-ordinator: Moray House Trust

Date: Friday 12 October 2012